The Romanies Have Come

An ancient part of European life

For centuries they’ve been viewed “askance”. I use that word because it sounds kinder than “viewed as a nuisance”. To this day, Europe’s bands of gypsies can expect a frosty welcome in the towns and villages where they pause in their wanderings. “Settled” people are apt to be set on edge by the Romanies’ presence. That’s certainly the widespread reaction this evening, in June of 1914. The gypsies, Zigani, Tzigani, Zingari, Zigeuner, Roma or Romanies – are widely distrusted, not altogether without reason. Yet, they’re an ancient part of European life, a fact that’s unlikely to change any time soon.

This Romany family has made camp alongside an arched railway ramp. If there’s rain or snow, they’ll move under the arches where the ceilings have become blackened by their fires through long years of visits. The police don’t bother them in their camps, but they keep a sharp eye on Romanies in towns and cities where they’ve been known to operate as pickpockets and other types of “nuisance”. In rural areas, horses, goats, chickens and vegetable gardens are watched closely when gypsies are passing through.

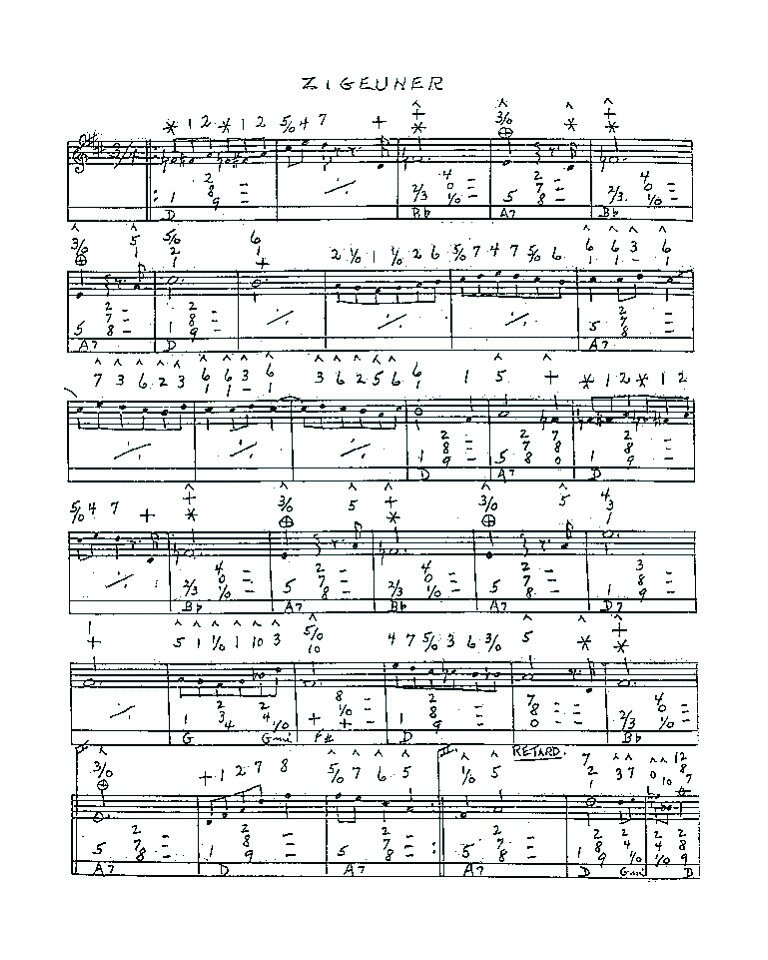

Still, they’ve given much to the cultures of Europe. Gypsy music and the styles of its playing have exerted pervasive influences on folk – and symphonic – compositions. Much-beloved Jewish folk music sprang from gypsy melodies … and vice versa. For centuries Galicia and The Bukovina – eastern provinces of Austria-Hungary – have been important centers of both Jewish and Romany life. The two cultures will continue to live there, side-by-side, until they’re devastated and scattered by the Nazis.

The grey two-seater belongs to the couple standing beside it. They’ve come to have their fortunes told, an age-old “service” offered by Romany women. Whether she uses tarot cards, kernels of maize (Indian corn), a pile of beans or traces the lines in their palms, she’ll speak softly, creating an authoritative intimacy while assuring her guests that she’s “seen” their futures, especially the pleasures that lie ahead. Just now she’s waiting inside the rustic caravan while her husband in his none-too-clean “gentleman’s” clothes invites the couple from the nearby town to climb the steps. On the wall beside the fortune-teller are posters current this month. The ocean liner is the “Aquitania”, launched in 1913, sister ship of the “Lusitania” that will be torpedoed and sunk next year by a German U-Boat, hastening the United States into the Great War. The other poster advertises “Réjane”, an aging, cheeky French music-hall star still popular in 1914.

The “seer” is holding a fully roasted chicken that probably came from a nearby farm kitchen. Today is, after all, a Sunday, and the chicken was probably being cooked for the family’s mid-day meal when a pair of gypsies distracted the cook while an accomplice removed the bird from the oven. It is a more common event than we might suppose, reminding us that Romany caravans had no ovens and theft was about the only way the Romanies might have come by a roasted chicken. Live fowl, and other meats, once killed, were always stewed in a pot over an open fire. Today’s chicken will be enjoyed as a rare delicacy.

The guests’ visit to the Romany “seer” would be viewed on this Sunday in 1914 as a daring, fairly exciting way to spend the evening – and to be parted from more of their money than they’re expecting. Outside the curtain at the back of the caravan, a young Romany girl waits to overhear the phrases auntie will speak to these stylish “clients”. She’s whispering with auntie about the chicken, knowing the clients will arrive within seconds inside the caravan. The pretty child knows that she’ll “inherit the business” and she’s already memorized most of auntie’s honeyed German words, though she isn’t too sure what some of them mean. The family converses in Romany and they speak Hungarian well enough, but they’re unlikely ever to become fluent in German.